How Bluey uses religious parables to teach lessons we all need

- Written by Sarah Lawson, PhD Candidate in Ancient Linguistics, School of Theology, Faculty of Arts and Education, Charles Sturt University

Bluey is a smart show that draws on all kinds of inspirations for its charming stories, including religious ones. My newly published research looks at what Bluey has to say about religion, and the religion of play which the characters live by.

Three episodes in particular show the diversity of religion in contemporary Australia and help us reflect on the diversity and depth of Aussie culture.

These episodes teach bite-sized lessons from real-life religions to children and parents in an approachable and thoughtful way. They reward curiosity and media literacy in a way which encourages parents to engage on a deeper level with their kiddo’s favourite shows.

So here’s what three episodes of Bluey say about religion – and the lessons they hold for children of any religion, and none.

The Buddhist parable

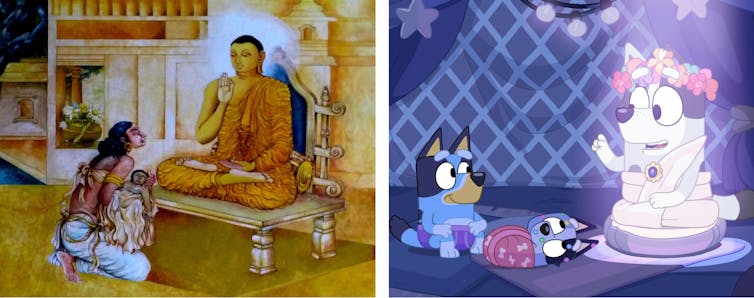

The episode Bumpy and the Wise Old Wolfhound is a not-so-subtle retelling of the Buddhist parable Kisa Gotami and the Mustard Seeds (but with the titular mustard seeds swapped out for purple underpants!).

In the episode, Bluey and Bandit make a video telling a story to cheer up Bingo, who is in hospital. In the story a woman called Barnicus has a puppy called Bumpy, who gets very sick. She takes Bumpy to the Wise Old Wolfhound for help. She is depicted sitting lotus-like, with robes made of towels and a flower crown.

The Wise Old Wolfhound asks for a pair of purple underpants from someone who has never been sick. When Barnicus can’t find anyone who has never been sick, she realises the Wise Old Wolfhound was teaching her everyone gets sick sometimes.

Sickness is just a part of life, and Bingo feels comforted that she is not alone.

In the original Parable of the Mustard Seeds, which dates back to the 5th century BCE, Kisa Gotami is a mother whose only son dies. When she goes to the Buddha for help, he tells her to gather mustard seeds from families in which there has never been death.

Through trying to complete this impossible task, Kisa Gotami learns death and suffering are inevitable.

Through retelling this religious story with its touch of humour and lowered stakes, children learn a basic Buddhist teaching. Sickness and suffering are terrible, but we can be comforted knowing that everyone goes through it, so we can let go of our attachment or need for constant happiness and wellness.

The Christian Easter

The episode Easter parallels some themes and images from the Christian Easter narrative.

Bluey and Bingo are worried that the Easter Bunny has forgotten them. Chilli and Bandit point out the Easter Bunny has already explained he would definitely come back on Easter Sunday.

That morning, the girls find empty egg buckets and must follow a trail of clues left by the Easter Bunny. They worry when they can’t find the chocolate eggs, especially when they need to be brave or suffer (going into Dad’s toilet). They worry they might be forgettable.

This parallels how the Christian religion teaches that Jesus’ followers thought God had forgotten them after Jesus died, despite the promise that Jesus had already given them that he would come back after three days. This teaching reflects the worry many folks feel, that they are maybe too insignificant or sinful for God to care about.

The episode ends with Bluey and Bingo rolling an exercise ball (stone) away from the desk cavity (tomb) to find the Easter Bunny had remembered them, cared about them and come after all to give them a wonderful gift of chocolate eggs (eternal life).

Through the slant telling of this religious story, children are encouraged to trust that they are loved and trust in the promises made to them – even when it seems like they’re small, forgettable or naughty.

The Taoist fable

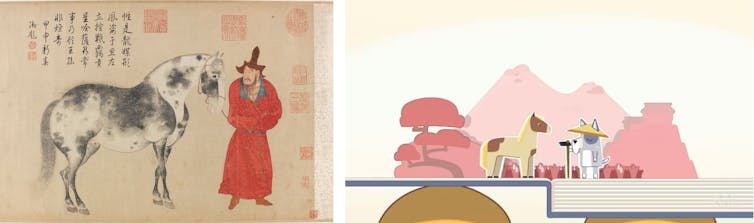

In The Sign, Bluey’s teacher Calypso reads a fable originally from the 2nd century BCE Taoist text Huainanzi. In English, the fable is often called The Old Man Who Lost His Horse, or A Blessing in Disguise.

The tale recounts a series of things that happen to this old man, and how, after each event, his neighbours tell him what good or bad luck that thing was. The Old man always responds, “We’ll see” in the wú wéi attitude. In the Taoist wú wéi view of fortune, all things are equal, and it is only human (or, in this case, canine) judgement that makes something good or bad.

Therefore, the only proper response to something dramatic happening is “inaction” or “serenity”, until the passage of time reveals the truth.

Horse and groom, by Zhao Yong 趙雍 (1291–1361); the Bluey episode The Sign.

National Museum of Asian Art, Ludo Studios

Horse and groom, by Zhao Yong 趙雍 (1291–1361); the Bluey episode The Sign.

National Museum of Asian Art, Ludo Studios

Bluey initially misunderstands the message, thinking Calypso means everything will go her way in the end. But by the end of the episode she learns to adopt the wú wéi attitude for the better. She remains calm, perhaps even serene, about the prospect of moving away from her beloved neighbourhood.

Through this religious story, children are taught that a gentle, flowing approach to life that doesn’t force one’s own desires onto the world can avoid unnecessary suffering and help us find peace and acceptance.

Authors: Sarah Lawson, PhD Candidate in Ancient Linguistics, School of Theology, Faculty of Arts and Education, Charles Sturt University

Read more https://theconversation.com/how-bluey-uses-religious-parables-to-teach-lessons-we-all-need-272070