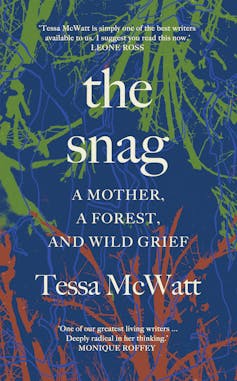

What can trees teach us about resilience and loss? A grieving daughter reflects

- Written by Gemma Nisbet, Lecturer in Professional Writing and Publishing, Curtin University

Tessa McWatt begins her new book, The Snag, on “the last day of the hottest year in recorded history”. In the previous two years, the Guyanese-born author has moved her elderly mother, who has developed dementia, from her beloved home and travelled between the United Kingdom, where McWatt lives and works, and Canada, where she grew up, to support her family.

At the same time, in other parts of the globe, people have been forced to leave their homes due to the effects of climate change — the scale of which registers as enormous, overwhelming:

The Cerberus heat dome enveloped Europe; British Columbia burned; wildfires raged everywhere there were forests; the Spanish Army was deployed to fight them; the Acropolis was closed; in China it was 52 degrees; and the British government gave the go-ahead for further gas and oil drilling in the North Atlantic. And somewhere between continents a daughter was crying as her mother was threatened with another move.

From her London home, McWatt, the author of a nonfiction book on race and several novels, asks herself: “Why bother?”

With that question, she wonders on her role as an individual and a writer to help effect meaningful change. It also points to another issue at the heart of The Snag: how to navigate grief, in all its multifaceted forms.

Trees: a model for human growth

In another early scene, McWatt travels to visit her family in Canada, where her ailing mother has moved to live with McWatt’s sister (an arrangement all the siblings agree on). Troubled by her mother’s distress at this change, McWatt takes an early morning walk in a nearby pine forest. In nature, she finds solace – but also something more.

Ontario is known for its white pines, trees that are so adaptable and resilient that seedlings from the southern part of the province do well in the north, even better than northern-born white pines. These trees will show me how resilience is possible.

McWatt begins to study trees “to uncover their secrets”. In their life cycles, she finds “a model for growth, for ways of being”. She writes: “Now that the world is more imperilled than ever before in human history, we can call upon the tree as a model of behaviour.”

Grieving the places we call home

Investigating the question of how we grieve, McWatt, a professor of creative writing at the UK’s University of East Anglia, adeptly connects the personal and the political, the local and the global. In doing so, she illustrates how they are inextricably linked.

Key to the book’s exploration of loss is its invocation of the notion of solastalgia – “the homesickness you have when you are still at home” – to describe a kind of environmental grief that acknowledges the importance of place, particularly the places we call home, to our sense of belonging, identity and wellbeing.

The associative, digressive qualities of McWatt’s prose evoke some of the sensation of what she calls “the newsfeed that has been looping in my brain”. We witness her fury and despair at the catastrophic effects of climate change and the way these effects are often most acutely felt by those most marginalised within global systems of power.

This feeling of powerlessness in the face of negative environmental change is part of what environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht aimed to describe in coining the term solastalgia.

It is fitting, then, that McWatt asks not only how we grieve, but also how it might prove generative. “How can this grief be transformed?” she asks. Answers, she suggests, can be found in forests.

The Snag argues the ways trees live and relate to one another might offer a regenerative alternative to the individualistic, capitalistic systems of value that are, the book suggests, the source of much of what plagues us. McWatt draws on the work of scientists such as Suzanne Simard, who have described the ways trees and plants communicate with one another, thriving in networks of complex interdependence. Of particular interest are trees at the end of their lives, known as snags.

Despite a snag’s inevitable death, its rich usefulness to wildlife is about to peak. Deadwood provides homes for insects and fungi. Those insects are food for birds, bats and other little animals, and these creatures shelter in the tree’s hollows and holes. They are in turn food for larger mammals and birds of prey. Dead, decaying trees are integral to a wood’s biodiversity.

This example suggests the systems of care that exist in forest ecosystems, which might inspire similar transformations in human societies, McWatt writes. Snags also offer possibilities for reframing death and loss, wherein ageing becomes “a triumph”.

Collective problems – and solutions

In exploring the entanglements of human and nonhuman lives, McWatt casts her net wide. She is particularly attentive to the cultural practices of Indigenous communities around the globe, as well as the ways they disproportionately bear the brunt of the effects of climate change. She also writes with an awareness that, as she notes, “some current conservation efforts displace people from ancestral homes”.

It’s difficult to encompass the scope of McWatt’s thinking here. In the space of a single page, she goes from drinking Californian wine by a Canadian lake while listening to the call of a loon, and thinking of a friend who has cancer, to reflecting on news of birds falling from the sky in India due to excessive heat, and remembering a visit to the Himalayas.

Elsewhere, she considers how notions of sacredness might meaningfully connect humans to the natural world, and finds joy in family celebrations and a burgeoning relationship with a man known only as “the musician”. She asks “what would the world look like if care became our organising principle?”