Nothing much comes of nothing in Belvoir’s new version of King Lear

- Written by Kirk Dodd, Lecturer in English and Writing, University of Sydney

Since its first performance in 1606, King Lear has earned its place as Shakespeare’s largest and most revered powerhouse tragedy.

The story follows an elderly King Lear (played in Belvoir’s new production by Colin Friels) who divides his kingdom among his three daughters according to their declared love. But he ends up rewarding his deceitful daughters Goneril (Charlotte Friels) and Regan (Jana Zvedeniuk) with powerful estates, while banishing his honest daughter Cordelia (Ahunim Abebe) for speaking plainly.

As Lear is betrayed by Goneril and Regan, his fragile mental state descends into madness. Civil war erupts and the body count grows before Lear learns, too late, how honest Cordelia was. The news of Cordelia’s death causes Lear to die of grief.

Unfortunately, despite an impressive cast and some outstanding performances, this Lear – directed by Eamon Flack, with the fuller title The True History of the Life and Death of King Lear and His Three Daughters – is as exciting as plain muesli or boiled cabbage.

The set, designed by Bob Cousins, consists of a sandy coloured floor with a chalk circle. Along one wall is a row of eleven chairs from the rehearsal room. It is as bland as untreated pine. And the costuming, by James Stibilj, is frustratingly mousy.

While pared-back may be a thing and dressing down can be a choice, it is difficult to understand the motives behind grey cardigans and full length brown frocks, or casual clothes that looked like rehearsal attire.

Striking images gone missing

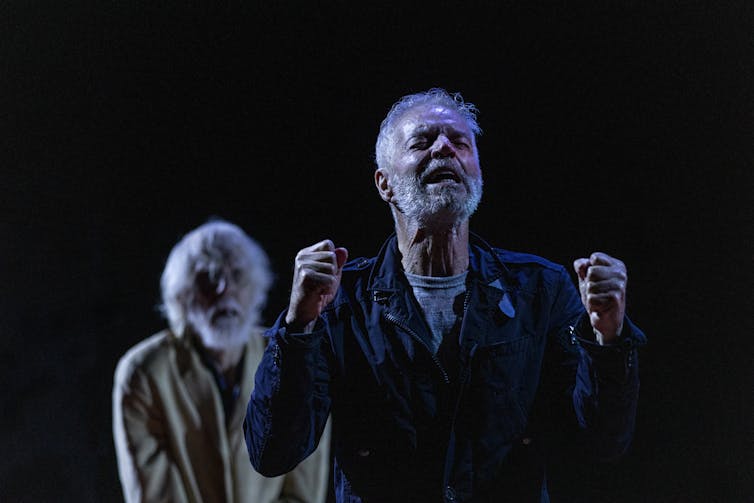

Shakespeare’s expansive play is replete with striking images and set-pieces that define its staging. The most vivid image is perhaps of a white-bearded Lear running outside at night to scream madly against a thrashing storm:

Blow winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow! You cataracts and hurricanoes […] You sulph’rous and thought-executing fires […] Strike flat the thick rotundity o’ th’ world […] Rumble thy bellyful! Spit, fire! Spout, rain! Here I stand your slave, A poor, infirm, weak, and despised old man.

There is the devilish embrace of Goddess Nature by Edmund the Bastard (Raj Labade) and Edgar the Legitimate (superbly played by Tom Conroy) escaping treachery by masquerading as a wild-man who “eats the swimming frog” and “drinks the green mantle of the standing pool”.

There is the brutal putting out of the eyes of Gloucester (Alison Whyte), and Edgar tricking his blinded father into believing he has jumped off the cliffs of Dover. And there is Lear’s fool (Peter Carroll), uncannily wise because he can show Lear his own folly.

The terrain is huge, and Lear’s fall from grace (and from his sanity) steep and grand, so there is much to contain upon the stage – but a bare-bones approach feels static and underwhelming.

An anticlimax

Minimalism is risky in Shakespeare, where most audiences haven’t read the play (or haven’t for a while).

Costumes help orient the audience and graft them intellectually to this strange and complex world. With so many characters (here, played by 13 actors), one might expect a sparkling crown or other status distinctions that could exude character. Instead, everyone fades away, and Lear is a king with a penchant for a blue Hans Solo jacket.

Such minimalism must be designed to place emphasis on Shakespeare’s language, but therein lies the risk.

In the program, Flack’s approach is overly fixated on circles. “Mathematically the centre of a circle has no dimension;” he writes

it is zero, nothing; and every other point in the circle, of which there are an infinite number, exists only in relation to that nothing at the centre […] This is the world of King Lear.

The play certainly has a philosophical regard for nothingness. Lear says, “Nothing will come of nothing”; Gloucester says “The quality of nothing hath not such need to hide itself”; and Lear says again, “Nothing can be made out of nothing”.

But it seems dangerously cerebral to bank everything on a neutralising treatment that can only result in the frustrations of anticlimax.

Shakespeare’s poetics lost

With the emphasis placed on delivering Shakespeare’s lines, Colin Friels’ Lear is robust and very well articulated. But his connections to the thoughts behind the lines can be patchy. While we hear the words, we don’t always comprehend their full eloquence and resonance. The lines seem often recited or mouthed with gravitas.

Excellent performances are provided by McClelland as the dutiful Earl of Kent, and Labade as a charismatic Edmund the Bastard, holding court with his soliloquies and asides.

Zvedeniuk plays a compelling Regan and Charlotte Friels is highly commendable as her evil sister Goneril.

Brett Boardman/Belvoir

Zvedeniuk plays a compelling Regan and Charlotte Friels is highly commendable as her evil sister Goneril.

Brett Boardman/Belvoir

Conroy is at first downplayed as Edmund’s legitimate brother Edgar, but then steals the show when Edgar becomes the destitute Poor Tom – a difficult role to execute.

Zvedeniuk plays a compelling Regan, switching allegiances on a dime, and Charlotte Friels is highly commendable as her evil sister Goneril, especially in two-hander scenes between the sisters.

It seems that realism jars against the minimalism, and Shakespeare’s poetics are lost in the exchange.

The True History of the Life and Death of King Lear and His Three Daughters is at Belvoir, Sydney, until January 4 2026.

Authors: Kirk Dodd, Lecturer in English and Writing, University of Sydney