a chilling new novel nails narcissistic tech culture

- Written by Caitlin Macdonald, Doctor of Philosophy (English) / PhD graduate / Researcher, University of Sydney

When I began reading Elaine Castillo’s Moderation, a new American novel about the psychological damage of online moderation, I had to pause. I’d read novels that confronted difficult material before, but this one blurred the line between bearing witness and re-enacting pain.

The book follows Girlie, a content moderator for a social media giant whose work requires her to watch and delete the internet’s most violent footage. Castillo threads this labour through a broader story of tech exploitation, immigration and the way empathy becomes a marketable skill.

I put it down, deeply uncomfortable, but also alert to the question: where is the line between necessary confrontation and unnecessary harm?

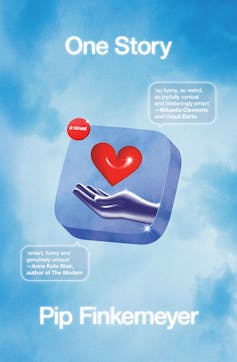

Review: One Story – Pip Finkemeyer (Ultimo)

That question lingered as I turned to Australian novelist Pip Finkemeyer’s One Story, a novel interested in power and performance that stages its discomfort through satire rather than shock. If Moderation displays to readers the brutality of what’s seen, One Story unsettles by showing us how violence can hide behind language – in self-branding and the performance of care.

Set between Silicon Valley, Bali and the digital ether of online mythmaking, One Story unfolds as a collage of interviews, transcripts, online threads and recollections from those who knew – or thought they knew – its central figure, Dot van Jensen.

Dot is the CEO of the eponymous storytelling platform. One Story is an app that promises to unify global narratives into a single daily story, “a sort of algorithmic scripture capturing the emotional pulse of the world.” She is also a master manipulator, narcissist, lover and mother: part tech visionary, part public scandal.

Tech’s golden girl

The novel opens, characteristically, in self-mythologising mode. “I was tech’s golden girl with golden hair,” Dot boasts. “CEO is my blood type.” In a few pages, she establishes herself as one of Finkemeyer’s most unreliable creations – a woman who, like the platform she builds, believes narrative is both currency and confession.

Confession as violence

Throughout, the novel plays with the idea that confession itself can be a form of violence. When its Campana Analitica scandal breaks, the company’s PR machine deploys the same placid, tech-bro tone used to describe their mission. Asked by a documentary producer about the human cost of their data leaks, Rae replies with deadpan sincerity: “We take user privacy seriously and have set up a taskforce …” The irony lands hard because it is so familiar, in its absence of feeling and routinisation of harm.

(Campana Analitica is a thinly veiled parody of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which a political consulting firm harvested Facebook user data to manipulate voter behaviour.)

In its final chapters, One Story becomes increasingly self-reflexive, blurring the line between the documentary’s gaze and Dot’s own attempt to narrate herself. As fragments of her story proliferate online, speculation replaces truth. Finkemeyer lets the noise build to an almost comic pitch, showing how, in a world saturated with storytelling, the self can vanish beneath its own narration.

Yet the novel resists pure cynicism. Beneath its biting humour and relentless irony is a sustained enquiry into what it means to live ethically in a culture that monetises empathy.

Dot’s company promises “one story a day” as if emotional attention could be quantified. But the narrative that emerges from the novel’s fragments – Dot’s childhood poverty, her fraught relationship with her son, Rae’s idealism corroded by proximity to power – suggests something more tender. Finkemeyer’s satire never forgets that these performances of self arise from longing for recognition and for control over one’s story.

Finkemeyer’s talent lies in her ability to make narcissism feel both grotesque and magnetic. The novel’s humour – its deadpan send-ups of startup jargon, its parodies of TED-talk sincerity – is so attuned to the rhythms of contemporary speech that it often feels documentary itself. Reading it is like scrolling through a feed that’s equal parts confession and advertisement.

Still, there are moments where the novel’s polish threatens to smooth over its emotional stakes. Finkemeyer’s control is so deft that her irony occasionally blunts the moral force of the work. The narrative’s self-aware commentary on storytelling as capital can feel overbearing. But perhaps this, too, is deliberate. The exhaustion we feel reading Dot’s voice, the repetition of slogans and spin, mimics the burnout of inhabiting digital life. Finkemeyer doesn’t just represent the attention economy; she recreates its seductions and its fatigue.

One Story is a unique kind of satire: one that is amusing, yet also profoundly sad. Its characters are trapped not by villains but by economic, technological and emotional systems that reward performance over sincerity. Dot, Rae and Jon each mistake narrative for connection. Their tragedy is not that they are monstrous, but that they are ordinary. As Dot says early on, defending her own myth: “The only thing I’m guilty of is becoming the person they so desperately wanted me to be.”

Finkemeyer brings us to a place of uneasy recognition. The cringe we feel at Dot’s arrogance, at Rae’s complicity, at the employees’ blind devotion is the pulse of the novel. It measures how thoroughly our lives have become entangled with the machinery of story.

I didn’t finish Moderation. Yet I finished One Story with a similar unease: not at what it depicted, but what it revealed. Finkemeyer exposes how power hides behind aesthetics and how empathy can be algorithmic. In the world of One Story, everything – including discomfort – is material.

Authors: Caitlin Macdonald, Doctor of Philosophy (English) / PhD graduate / Researcher, University of Sydney