A 1980s cost-of-living crisis gave Australia a thriving arts program – could we do it again?

- Written by Izabella Nantsou, Academic in Theatre and Performance Studies, University of Sydney

The cost-of-living crisis is hitting the arts hard. Artists struggle to survive on poverty wages and audiences are getting priced out.

This challenge is not unprecedented. In the 1980s, another cost-of-living crisis sparked a bold and imaginative model for embedding artists into the everyday rhythms of working life.

Art for the working class

It was 1982. The country was in the grip of stagflation: low growth, high inflation and rising unemployment. The Australia Council for the Arts was reconciling a 20% funding cut. Seeking to offset its cut funds, the council sought out an unexpected partner to launch a community arts program: the Australian Council of Trade Unions.

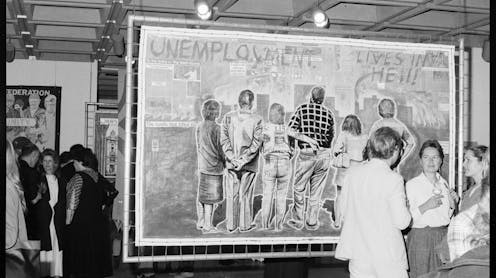

The “Art and Working Life” initiative sought to celebrate, encourage and support working class art and culture. By embedding artists in workplaces across the country, it enabled workers to practice and develop their artistic skills and expression.

It also addressed two key issues: employment for artists, and increasing the public’s access to the arts.

Unions would sponsor projects and act as employers for the artists involved throughout the project’s duration. This arrangement placed artists in diverse settings such as factory floors, hospital wards, offices and construction sites, where they collaborated with workers to create art that reflected the realities of their working lives.

Why trade unions?

In 1982, 57% of Australian workers were unionised. This meant unions had the infrastructure to match the government’s funding through the Australia Council, and to employ artists on a project basis.

With union membership mandatory in many industries, this generated a guaranteed resource base capable of funding an arts program for the broader community. For artists, the unions’ reach into various industries provided significant potential audiences.

Unions offered more than resources; they brought a philosophy and a plan. Art was a cultural right. In workplaces, it could lift morale, disrupt the grind and add meaning to labour.

It also had practical benefits: strengthening workplace culture, engaging members and helping artists organise within their own industry.

Art and Working Life projects varied widely. Dancers in garment factories devised movement routines aimed at reducing repetitive strain injury. In rail yards, theatre artists wrote plays in collaboration with engineers and mechanics about gender, race, and labour. Musicians headed underground – literally – to record original songs written by miners about the threat of job losses.

By 1986, Australia Council chair Donald Horne lauded the program as “a good example of value for money”.

In four years, it reached over three million workers and their families – nearly 20% of the population – at a cost of just A$2.8 million (around $9 million today).

By the end of the decade, it had employed more than 2,000 artists, with union support matching federal funding.

A slow decline

But the program depended on two fragile pillars: a strong labour movement and sustained government support.

By the 1990s, both were under threat.

As privatisation, deregulation and enterprise bargaining eroded union power, membership declined, workplaces fragmented, and the foundations of Art and Working Life weakened.

At the same time, a major shift occurred in arts funding. In 1994, Paul Keating released Australia’s first national cultural policy Creative Nation, reframing the arts as an economic driver, emphasising export-ready, profitable outcomes. Arts funding increasingly favoured media, tourism and “creative industries”.

For the Australia Council, this shift meant a retreat from community arts programs like Art and Working Life, and the program was quietly shelved in 1995.

It marked more than the loss of a funding stream: it signalled the decline of a cultural policy vision grounded in social equity and everyday life.

Would it work in 2025?

Today, with union density hovering around historic lows of 13.1%, the infrastructure that once supported a national workplace arts program is largely gone. But the need is as urgent as ever.

In the face of today’s cost-of-living crisis, we need bold, integrated policy frameworks with a strong social foundation. Australia’s current cultural policy, Revive, was released in 2023. The document signals a rhetorical shift away from economic metrics and towards access and inclusion. But what structures bring this vision to life?

Today’s cost-of-living crisis could be used to inspire a new wave of cultural investment that supports employment, fosters participation and embeds creativity in everyday life.

Looking at the history of Art and Working Life offers more than nostalgia: it provides a practical model for anchoring arts policy in the material conditions of working people’s lives, where the arts are not apart from daily experience, but central to it.

Authors: Izabella Nantsou, Academic in Theatre and Performance Studies, University of Sydney